Big bluestem, bigger dreams

K-State Goldwater Scholar leads study of one of North America’s most important grasses

By Emily Boragine

By Emily Boragine

K-State News and Communications Services

For Helen Winters, her K-State classroom and research site has been in 26 different locations across 22 U.S. states.

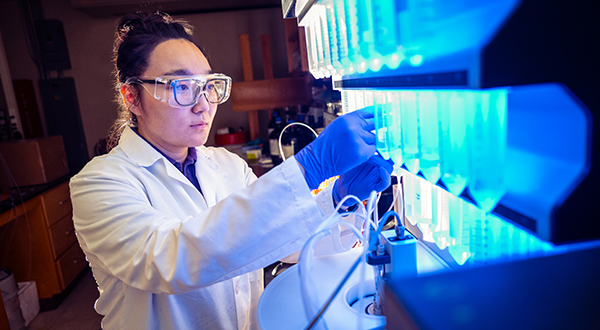

Winters is a senior studying biology and fisheries, wildlife, conservation and environmental biology. She is the university’s 82nd Goldwater scholar and is about to lead a multi-year research project on climate adaptation in 26 populations of big bluestem grass — one of the most common and crucial grasses in the prairies and plains of North America.

An initial interest in plants and animals as a curious undergraduate led Winters to become a key contributor in a comprehensive research project started by doctoral student Jack Sytsma in the lab of Loretta Johnson, a professor of biology.

The project, which is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, seeks to model and predict the potentially significant ecological and agricultural impacts of climate change on big bluestem. That work could then inform future conservation efforts and contribute to more effective strategies amid changing climates.

Helen and Jack traveled to 26 sites in 22 states, from Michigan to Louisiana and Colorado to North Carolina, to study big bluestem across its range. They observed significant variations in the species.

In drier western regions, big bluestem tended to be smaller with higher photosynthetic rates and greater drought tolerance, while on the eastern

edge, it grew larger but with lower photosynthetic rates and drought tolerance.

To determine if these observed differences are genetic or environmental adaptations, the team collected seeds from the various populations and planted them in a K-State greenhouse under strictly controlled conditions to understand the variations and what causes them.

The researchers also took the samples to four sites — Colby, Hays and Manhattan, Kansas, and Carbondale, Illinois — that were selected for the wide range of annual rainfall they each receive. The team will track how these different big bluestem populations respond or survive, which will provide an understanding of how big bluestem populations have adapted.

“Depending on how many plants survive, it could be around 156 plants per site, which is a lot of work to measure, especially considering the site we have in Illinois,” Winters said.

“I want to do something that’s a bit different than what has been done in years past. And I’m slowly figuring out what that’s going to be.”

Along with mapping and modeling the effects of climate change on big bluestem, the team is also working to develop recommendations for restoration and conservation practices to mitigate those effects.

One tactic could include transplanting populations of drought-tolerant big bluestem from western regions into eastern areas where drought is predicted.

As the team gains a deeper understanding of the vital tall grass, Winters is committed to advancing the research, while developing her own skills as a researcher.

“I want to do something that’s a bit different than what has been done in years past. And I’m slowly figuring out what that’s going to be,” she said.