Entomologist is working to save the honeybee and solve red meat allergy

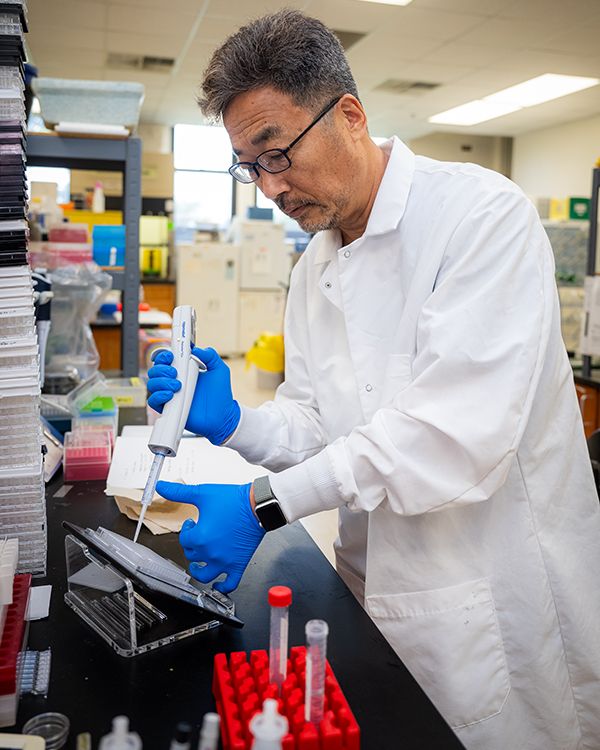

Yoonseong Park, university distinguished professor of entomology, is a world-renowned expert in the molecular physiology of arthropods.

By Michelle Geering

By Michelle Geering

K-State News and Communications Services

Saving honeybees and solving the mystery behind red meat allergies are two of the world’s most perplexing insect-related challenges.

Yoonseong Park is working on both.

Park, university distinguished professor of entomology in the College of Agriculture, studies the molecular physiology of arthropods — including creatures like insects, ticks and mites — to improve human life.

Park is researching solutions to keep honeybees and their hives free of Varroa mites, which feed on the bees and spread viruses within the colony. Using genome sequencing, Park aims to develop a control agent that will kill Varroa mites without harming honeybees or humans.

“The Varroa mite problem is a worldwide issue, and they are the No. 1 enemy of the honeybee,” Park said. “We have been studying insect and acari genome sequences for a while to identify potential targets that are only harmful to the pests.”

That sequencing work led to a breakthrough in which Park found a Varroa mite-specific neuropeptide that could be targeted with a pesticide — a discovery for which he was awarded an international patent. Park continues to test a chemical compound and application strategy to keep bee colonies free of mites and their viruses.

While saving the honeybee is a passion of Park’s, he is equally passionate about understanding the leading factors for alpha-gal syndrome, or red meat allergy.

Alpha-gal syndrome was first identified and studied in the early 2000s. Scientists know bites from the lone star tick, primarily found in the U.S., can cause the meat allergy, but not everyone with this type of tick bite develops it. Park is working toward understanding why some people remain unaffected, while others develop alpha-gal syndrome.

The entomologist is looking for distinguishable markers in both tick saliva and human blood samples to better understand the syndrome and how it manifests. Park has found that when ticks feed on human blood, allergen production incidence significantly increases compared to when ticks feed on the blood of other animals.

“There is great satisfaction in finding a solution by thinking about a problem, and research allows me to do that.”

Park also examines human blood samples to identify genetic markers that may indicate if a person is susceptible to developing alpha-gal syndrome.

Pests can be harmful to nations’ economies, industries and human health. Finding a new method or technology for controlling pests continues to drive Park forward in his work.

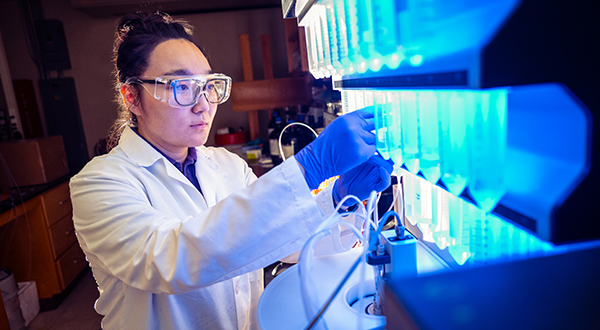

The next pest or insect challenge could be just around the corner, and Park recognizes the need to help develop the next generation of great entomologists.

“There is great satisfaction in finding a solution by thinking about a problem, and research allows me to do that,” Park said. “It is also invigorating to work with young scientists who are ambitious and energetic.”