K-State research is creating a process to guarantee honey is pure — bee-yond a doubt

Through a new industry partnership, K-State is creating buzz as the next-generation land-grant university for honey production research and engagement.

he eye-opening stat isn’t that the U.S. consumes about 600 million pounds of honey each year, but that some of it might not even be honey.

Only about 125 million pounds of the total amount is produced in the country, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. The rest is imported, and some of those imports have been found to be adulterated with cheap sweetener ingredients. In fact, honey is the third most economically-motivated adulterated commodity in the world.

When consumers buy honey at the store, there is not an independent certifying agency or organization that can help them make informed decisions about their purchase. In contrast, a steak at the grocery store is probably clearly marked and certified as USDA Prime, Choice or Select.

This potential for honey adulteration is a problem for both American honey producers and consumers, but one Kansas State University research is poised to help solve.

As part of a partnership between K-State, the American Honey Producers Association and the locally-owned and veteran-managed Valor Honey, the newly-forming American Honey Institute will create independent testing services to support ongoing certification efforts to recognize pure, unadulterated honey, said Brian McCornack, K-State entomology department head and director of the institute.

The partnership will also help promote beekeeping, both as a business and as a skill.

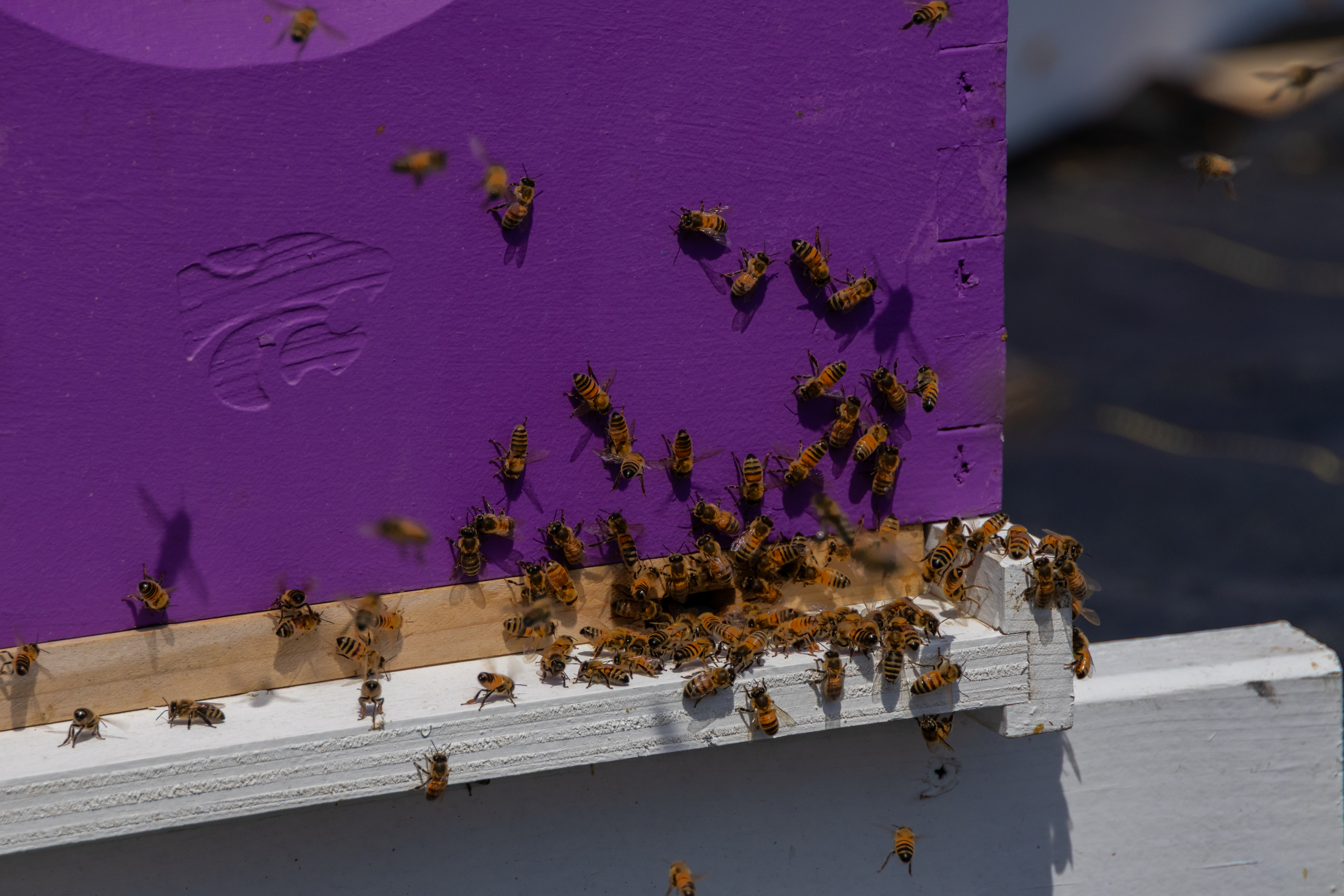

Maintaining a healthy population of pollinators is a monumental task, McCornack said. Honey bees are America’s primary commercial pollinators and are regularly transported around the country to provide their crucial services for dozens of crops that go towards feeding the nation. Pollinators add more than $18 billion in revenue to crop production every year, according to the USDA.

"Bees are livestock, and just like the cattle and chicken industries, we need to make sure we have a robust domestic production system that keeps beehives buzzing and producers in business," said McCornack.

Through partnerships with industry partners under the American Honey Institute at K-State, students in the entomology department's beekeeping course are getting hands-on, applied learning in one of the agriculture industry's most critical stages.

Pure honey, bee-yond a doubt

While the U.S. honey industry already sets some standards for its products, only a few hundred samples from the millions of pounds of honey imported into the country each year are tested by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. That creates an opportunity for fraud.

While American honey producers might need to charge between $3-4 per pound of honey to reflect the tremendous amount of work necessary to create each sweet drop, McCornack said, honey adulterated with cheap sweeteners like rice or corn syrup can enter the market at less than $1 per pound, making it difficult for American honey producers to make a profit.

The mismatch puts U.S. honey producers at a disadvantage, and it leaves honey consumers unsure of who or what to trust when it comes to buying the natural, golden sweetener.

“When in doubt, buy from local beekeepers,” McCornack said. “Combating this issue at a national level requires more coordination across the industry, including an updated definition of honey.”

Looking for a solution, the American Honey Producers Association recognized K-State as an institution that could develop and help implement a transparent, independent honey certification process.

“This work is about solving tough challenges by finding people who are willing to take them on,” McCornack said. “At K-State, we like to tackle and solve these big problems — it’s what we do.”

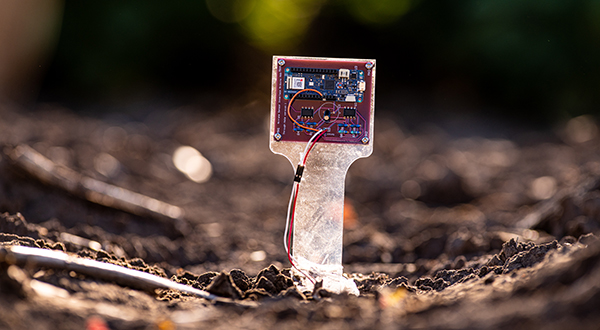

Through the American Honey Institute, McCornack and his team are developing a testing program across multiple organizations that honey producers could use to help their customers know exactly what they’re buying, selling or eating. It could also support existing certification programs by providing independent audits through a network of land-grant institutions.

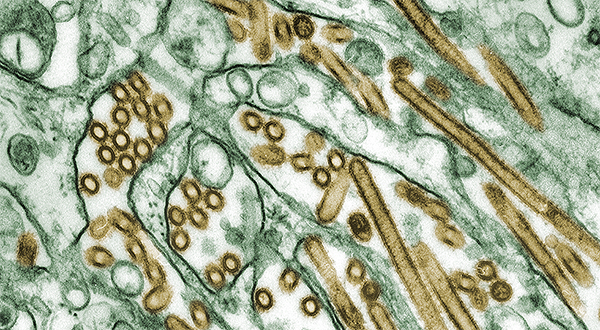

The process consists of a system of checks and balances that analyzes honey products to determine and certify that samples contain appropriate nectar types and pollen sources — just the way the bees made it.

That would help provide a unified, transparent way for consumers, producers and retailers to communicate about the quality and origin of their honey products, strengthening the integrity of the honey supply chain.

“Let’s make it clear for people: this is honey, and here’s exactly what’s in it,” McCornack said.

Serving something bigger

K-State is also playing a significant role in the American Honey Institute by educating the next generation of beekeepers, while also developing training opportunities for current military service members and veterans.

Thanks to support from the university, the entomology department was able to purchase its first colonies of honey bees to start a basic beekeeping course at K-State in the spring of 2024.

Retired U.S. Army Col. Gary LaGrange of Valor Honey has been a key partner in the American Honey Institute and has helped co-teach K-State's beekeeping course.

While many of the students in the courses are entomology majors, others come from various backgrounds like business, biology and English.

“We couldn’t start the education component until the colonies were purchased,” McCornack said. “Two years in, students are walking into their beekeeping final with smiles on their faces, saying, ‘I’ve been looking forward to this all week.’”

Over the past few years, K-State has also worked closely with retired U.S. Army Col. Gary LaGrange of Valor Honey.

The nonprofit — a local veteran-managed honey producer — has trained hundreds of veterans, and it has especially helped veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“We’ve seen firsthand how working with bees can help veterans who are struggling,” McCornack said. “They gain a sense of purpose. And for some, it’s life changing.”

“If K-State can help American honey producers succeed, we can keep our pollinators—and our food—secure.”

Although better quality honey and beekeeping practices is one goal of the partnership, other aims include understanding the potential effects of mass honeybee losses and building knowledge on how to keep colonies healthy.

Bees help ensure that the pollinated plants and crops the U.S. depends on for food thrive, McCornack said. Such crops are often more nutrient-dense, and without bees, a serious food security crisis could ensue.

“We must think ahead to keep this industry viable while protecting native bee species as well,” McCornack said. “The pollinators that we rely on for food production are at risk. But we can make a difference. If K-State can help American honey producers succeed, we can keep our pollinators—and our food—secure.

“It’s not just about our honeybees being successful. It’s about making connections, growing together and strengthening an industry.” ![]()

◊◊◊