Dealing with a dairy dilemma

K-State research has been crucial to understanding highly pathogenic avian influenza in the dairy industry and developing strategies to limit its spread.

uring the last two years, strains of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, or HPAI — otherwise known as bird flu — have been wreaking havoc on populations of wild birds, first in Europe and later in the United States.

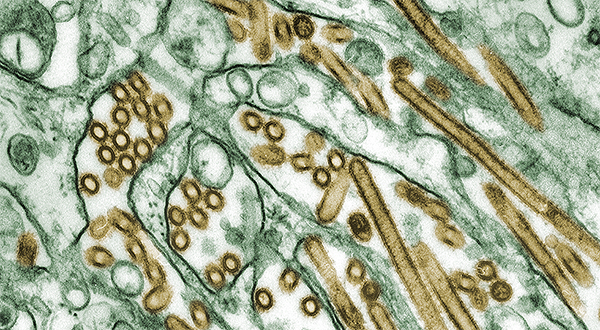

Veterinary researchers have long known that H5N1, the virus that causes HPAI, rapidly spreads among flocks of birds. But when the virus was suddenly detected in cattle in spring 2024, the researchers were stumped that it also seemed to spread rapidly in the bovine population. More than 200 dairy cattle farms in 14 states have seen the spread of HPAI in the year since.

The H5N1 virus.

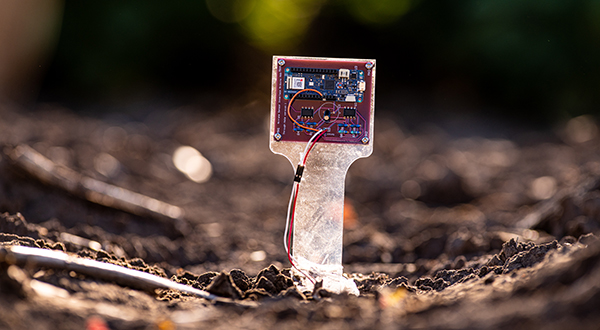

The connection between birds and cattle was not immediately apparent, but researchers in the Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine have discovered a surprising reason for the spread of this disease among dairy cattle: the act of milking.

“Milking equipment and anthropogenic activities were suspected to be involved in the transmission of H5N1, but clear evidence of the mode of transmission had been lacking,” said Jürgen Richt, university distinguished professor in diagnostic medicine and pathobiology and a preeminent global researcher in zoonotic diseases.

Richt’s findings were published in a paper last fall in Nature, one of the world’s most prestigious academic journals.

In a collaborative effort, research teams — led by Richt and Martin Beer from the Friedrich Loeffler Institut in Germany — conducted studies on both calves and lactating cows using the H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b virus, the strain of the virus circulating in cattle in the U.S., to gain insight into likely modes of transmission.

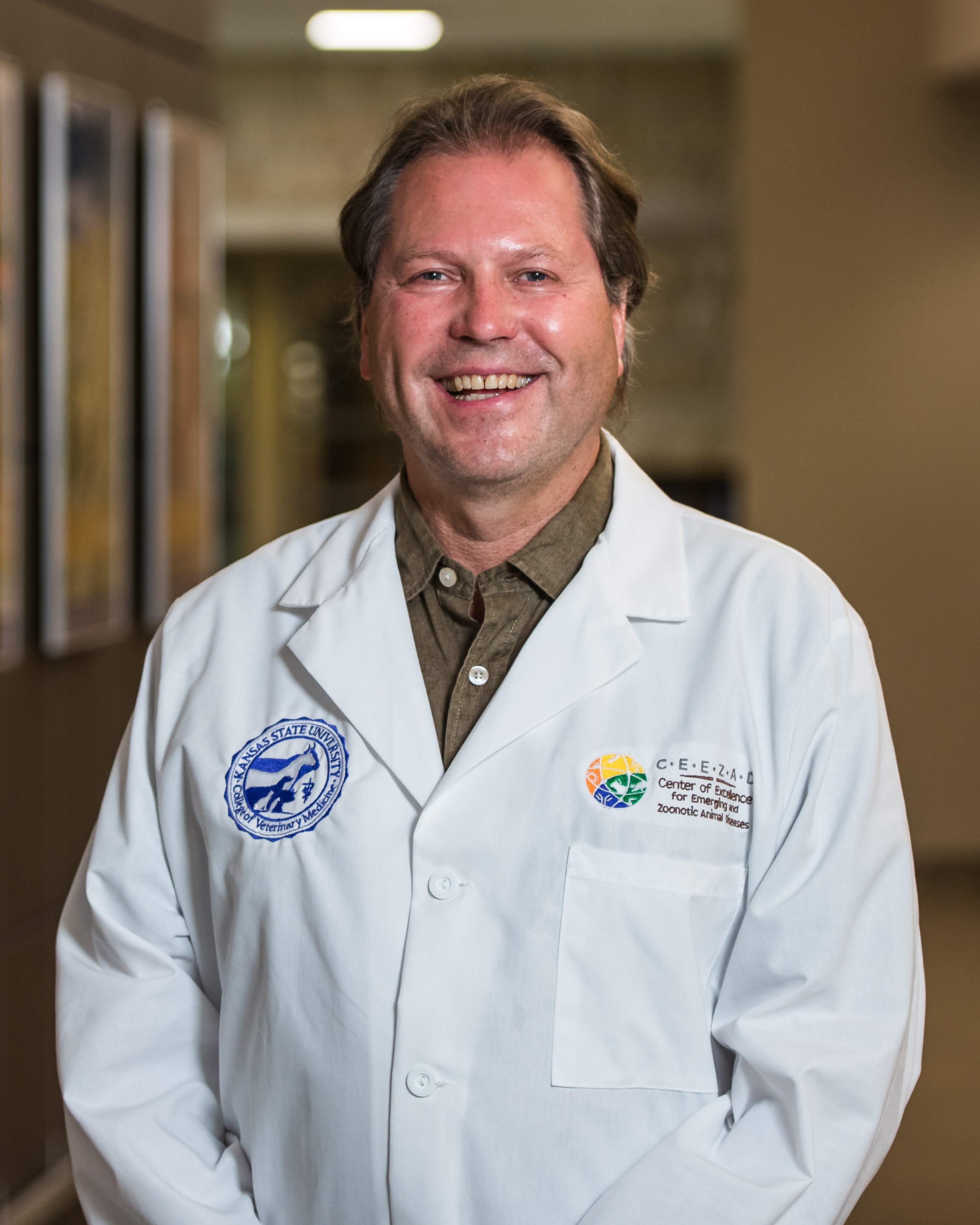

Through his team of researchers like graduate research assistant Chester McDowell, Jürgen Richt has made significant breakthroughs in understanding the spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, or HPAI.

Pinpointing the means of transmission

The findings indicated that the milk and milking procedures, rather than respiratory spread, are the likely primary routes of H5N1 transmission between cattle.

“There are nearly 10 million dairy cows in the United States today. It is imperative that we study the ways this new disease transmits in them,” Richt said. “Given the potential economic damage to the cattle industry and risk to human health presented by bovine H5N1, this research shows that establishing safe, sanitary milking procedures is a topic of substantial concern within the U.S. dairy industry.”

The study was funded in part by the State of Kansas National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility Transition Fund, and the animal research was conducted at K-State’s Biosecurity Research Institute and the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut in Germany.

It is another example of Richt’s extraordinary ability to orchestrate an international collaboration to provide answers regarding viral transmission within months of new disease recognition, said Bonnie Rush, Hodes family dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine.

“Similar to COVID-19, this Nature publication is a shining example of the expertise of this research team to rapidly pivot resources and deliver relevant data in response to an emerging zoonotic disease,” she said.

Further findings

Richt’s team and collaborators have also been investigating other aspects of HPAI transmission.

Richt is director of the Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, which specializes in this type of research.

Because of the biosafety level-3 laboratories and research capabilities at the Biosecurity Research Institute, K-State is the premier institution to handle the investigations of these types of outbreaks, he said.

“We have established a team that can do this type of research,” Richt said. “We are well trained and we know how to handle all the aspects that are involved in a high-containment research environment.”

“There are nearly 10 million dairy cows in the United States today. It is imperative that we study the ways this new disease transmits in them.”

Richt’s team moved quickly to publish findings in connection with HPAI. In September 2024, the team published a paper in the journal Viruses, which detailed two methods to inactivate the virus. A key finding involved the persistence of the HPAI virus in lactose byproducts that are used in animal feed products.

The team also published a separate paper in Virus Genes that discussed the rapid evolutionary progression of H5N1 in dairy cattle, underscoring a critical need for enhanced epidemiological monitoring of the disease.

Although much of the research has focused on dairy cattle, Richt said the research’s applications are not limited to cows.

“We have done experiments with pigs as well,” Richt said. “It’s good news for the swine industry. There’s not much happening with this virus, but we still need to be vigilant.” ![]()

◊◊◊

Richt — a Kansas regents distinguished professor, a university distinguished professor in diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, and a Kansas Bioscience Authority eminent scholar — was among 90 regular members and 10 international members who were elected to the academy in his cohort. Election to the academy recognizes Richt as a pioneer in infectious diseases of One Health importance, with research on zoonotic pathogens — infections that can be transmitted from animals to humans — that has led to significant findings for both animal and public health. “We are incredibly proud of Dr. Richt for this remarkable accomplishment,” said Hans Coetzee, interim vice president for research at Kansas State University. “Being selected to join the National Academy of Medicine is a testament to his outstanding contributions to the field and his dedication to advancing medical science and improving healthcare.” In October 2024, Richt was elected as a member of the National Academy of Medicine — one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine.

In October 2024, Richt was elected as a member of the National Academy of Medicine — one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine.