The next generation of great mathematicians is Navajo, and K-State faculty are inspiring it

Tuesday, June 25, 2024

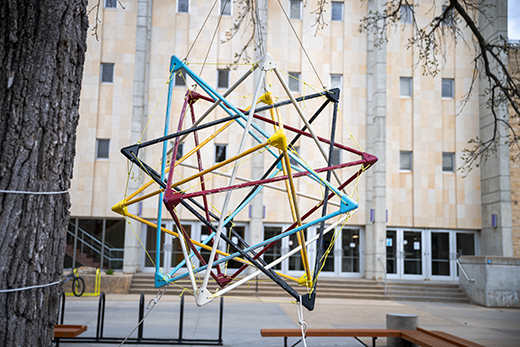

As part of the Navajo Nation Math Circles program, Dave Auckly and other mathematicians use activities like dissection puzzles, which involve rearranging parts of a polygon into a different polygon, to teach critical thinking and puzzle solving skills. | Download this photo.

MANHATTAN — Imagine wanting to become a basketball player but only being able to read about the theory of dribbling and shooting, never or only rarely touching a basketball.

Or wanting to become a concert pianist but never feeling the weight of a single key or hearing the harmonic ring from it rebounding against a tightly wound set of piano strings.

It doesn't make sense, right?

Dave Auckly doesn't think so. That's why he and several other Kansas State University mathematics faculty and staff collaborate with the Navajo Nation Math Circles on a mission to inspire a love and appreciation of math in preK to high school students and help them find the joy in solving puzzles, particularly in Indigenous communities in Auckly's home state of Arizona.

Since 2012, Auckly has been director of the Navajo Nation Math Circles, an outreach program that brings in 80 to 100 visitors from around the U.S. and the world to help share their talents and love for math.

The program is a mixture of outreach visits and workshops in schools and other community centers by mathematicians during the school year. But one of the program's most significant outreach services is a two-week summer camp that hosts dozens of middle and high school students.

"People come and contribute their time, effort and sometimes money to make what can be a very isolated place into something magical for the students," Auckly said.

As part of the Navajo Nation Math Circles program, Dave Auckly and other mathematicians use activities like dissection puzzles, which involve rearranging parts of a polygon into a different polygon, to teach critical thinking and puzzle solving skills. | Download this photo.

Bringing math education full circle

Math circles, Auckly said, are a concept that dates back a century in eastern Europe, when Soviet leaders wanted to develop the next generation of great mathematicians, scientists and engineers.

The point is to learn to face a problem, to think through it and then to understand, Auckly said — to put in practice the math skills they might have read or talked about in school.

"Math circles are programs where a group of people — and they don't need to be the same grade level — come together to explore mathematics because they want to, and because it's fun," Auckly said.

The concept later spread to other parts of Europe, especially countries where school ends very early in the afternoon. Math circles served as a way for people with common interests to get together, the same way others might gather to make informal music or play sports.

"It's been going for 100 years, and you see it in the resulting level of mathematics that comes from these groups," Auckly said.

Math circles were slower to grow in the U.S., but Auckly, who has been involved in math outreach his entire career, is one of many who wanted to help expand the concept.

As part of the Navajo Nation Math Circles program, Dave Auckly and other mathematicians use activities like dissection puzzles, which involve rearranging parts of a polygon into a different polygon, to teach critical thinking and puzzle solving skills. | Download this photo.

From 2009 to 2012, he served as associate director of the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute — one of a handful of National Science Foundation-funded math research institutes. While the institute undertook and encouraged math research, it also had a significant outreach portfolio, and Auckly used his time at the institute to grow the concept of math circles. He said that when he started in 2009, there were about 20 math circles around the U.S.

By the time he left three years later, there were about 150.

Granted, the job of mathematician will hardly make most kindergarteners' top five most-desired careers. But the point of a math circle isn't to funnel students into degrees or jobs solving equations on dusty chalkboards.

The problems and puzzles that students might encounter in a math circle are all meant to have a low floor, so that everyone can at least understand the question. Think puzzles, toys and activities like Rubik's cubes and sudoku.

However, the puzzles and activities gradually become deeper, so students begin seeing "beautiful patterns and things that are surprising and engaging and thought-provoking."

"It's really captivating for a lot of people," Auckly said. "You need to have an appropriate mix in math where people can see the beauty, the exploration and the artistic elements of the field. Sure, there are some algorithms that people do need to master to understand and learn more. But you need to have both kinds of appreciation."

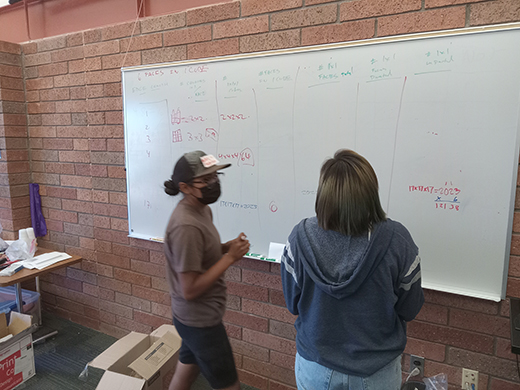

Students Hailee Martin and Rena Segay work on a geometry/counting problem at the 2024 Navajo Nation Math Circles summer camp. For the past decade, K-State's mathematics faculty have traveled to the Southwest to lead activities and education through the Navajo Nation Math Circles outreach program. | Download this photo.

Numbers in the Navajo Nation

During his time at the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, Auckly had been assisting with math competitions in the San Francisco Bay Area when someone knocked on his office door and changed his life.

It was this remarkable woman, Tatiana Shubin — whom Auckly described as a wonderful mathematician — who came to him with the idea to do math outreach in the American Southwest.

She had been doing this type of work already, both in her home country in the former Soviet Union and in her new home in the U.S., where among other things she created the first math circle for teachers.

The pair used their connections to meet people and understand the needs of the Navajo Nation. The sovereign tribe — spanning much of the northeastern corner of Arizona and parts of New Mexico and Utah — faces many of the challenges that many rural U.S. states do, particularly poverty and low access to resources such as education and internet connectivity.

"For the longest time, I thought about the statistic that about a third of Navajo households did not have electricity," Auckly said. "More probably have it now, since there have been big electrification efforts in the years since, but electricity, as well as the internet, have struggled to serve the community."

After months of meeting with leaders and local teachers across the nation, Auckly and Shubin gained trust and buy-in from communities. In 2013, the program ran its first math festival and first summer camp.

"Even if these kids don't become math majors or do more with it after high school, they're thinking about academics in a different way, or what it's like to engage with their schoolwork," Kim Klinger-Logan said. "They might even be thinking for the first time about how they could apply these skills in college." | Download this photo.

"After we started, the students couldn't get enough," Auckly said. "In the early days, about half of the students would come back, and they would bring friends, and then other friends would hear about it, and then their teachers would. Word-of-mouth was an important mechanism for us back then, as it is today."

Today, the Navajo Nation Math Circles' summer camp hosts about 30 to 50 students each year, although Auckly wants to continue growing the camps and outreach. Dozens of math visitors, like K-State math professors Kim Klinger-Logan and Misha Mazin and others at institutions around the world, help facilitate math lessons and activities at the camp and in workshops.

The main challenge for the program is in logistics, especially for outreach beyond the summer camps. A school might request Auckly or another speaker to come visit with a week's notice, but it's not easy to arrange hundreds of miles of travel on short notice.

They're able to work closely with students and inspire an appreciation, or maybe even love, for a subject that they didn't have before.

"Even if these kids don't become math majors or do more with it after high school, they're thinking about academics in a different way, or what it's like to engage with their schoolwork," Klinger-Logan said. "They might even be thinking for the first time about how they could apply these skills in college."