Nearly 70 years later, Harold and his purple crayon still teach plenty, K-State professor says

Friday, Aug. 2, 2024

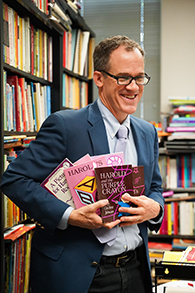

Kansas State University distinguished professor Philip Nel is the author of an upcoming book examining the legacy and surprising nuance of children's literature classic "Harold and the Purple Crayon." | Download this photo.

MANHATTAN — Ever the curious and inventive 4-year-old boy, Harold never had much to say, but that was the point.

As long as he could imagine it, any challenge could be overcome with the simple stroke of his trusty purple crayon, which he did several times over the course of seven books in Crockett Johnson's popular children's book series launched by "Harold and the Purple Crayon."

It's an ode to creativity that has inspired millions of children and adults over the past seven decades, including Philip Nel, university distinguished professor in Kansas State University's department of English.

Nel is the author of "How to Draw the World: Harold and the Purple Crayon, and the Making of a Children's Classic," a book that will be published later this fall by Oxford University Press. It will be the first of the publisher's upcoming series Children's Classics Critically.

That series, which Nel will co-edit with friend and colleague Melanie Ramdarshan Bold of the University of Glasgow, will aim to analyze both historic and contemporary staples of books for young readers.

There is plenty of interest in revisiting some of these classics, Nel said, both from researchers and adults who want to think through some of the most memorable books from their childhoods from a more modern viewpoint.

But Nel is excited to kickstart the series with one of his personal favorites.

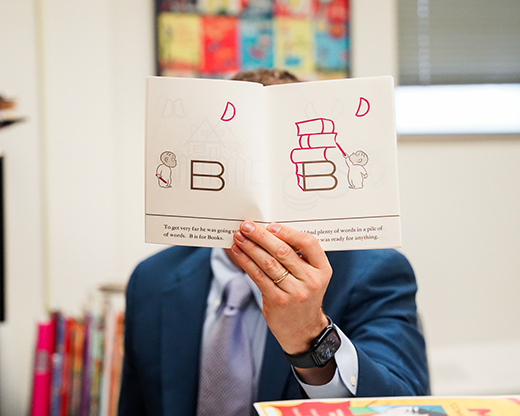

Part of the enduring appeal of "Harold and the Purple Crayon" is that every kid — regardless of gender or ethnicity — can see themself in the four-year-old's shoes, said Philip Nel, university distinguished professor of English. | Download this photo.

"I had long thought that it would be a great idea to do a small book on this smaller one because it would be an occasion to invite people to look closely at children's books," Nel said. "'Harold and the Purple Crayon' is a perfect example because it appears so simple. What more could you say about a boy and a purple crayon? But there's actually a lot, from the design of the book to its philosophy of creativity."

As a children's literature expert, Nel said the genre has too often been overlooked as too simplistic or "juvenile" to qualify as art or serious literature. Scholarship and research in the field has only picked up in the last few decades, and university courses like the ones he and his colleagues now teach were more rare when he was an undergraduate.

But children's literature, as a simple and relatively fun genre, is also one of the most critical.

"Children's literature is the most important literature that we read because we read it when we are learning who we are and whose stories matter, and when we're forming our opinions about the world in which we live," Nel said. "It's a type of literature that can potentially have the largest impact upon a developing self."

That impact is reflected in the ongoing popularity and continued adaptation of children's books like "Harold and the Purple Crayon." The book, which has been transformed into a television show and stage play in the decades since its 1955 publication, was recently adapted for the first time as a major motion picture that premieres Aug. 2.

Why did Crockett Johnson choose the color purple for Harold's crayon? Philip Nel could only find one time the author ever addressed the issue. "He told his interviewer, 'Purple is the color of adventure,'" Nel said. | Download this photo.

Nel said he is curious about how the book will adjust to fit a 90-minute runtime. Even at just 64 pages of a sentence or two each, Crocket Johnson wove a cohesive and imaginative narrative that has resonated with children and acclaimed artists like musical genius Prince, Caldecott award-winner Chris Van Allsburg (Jumanji) and Pulitzer Prize-recipient novelist Richard Powers.

"The whole book is a giant mural, really, that is revealed a page or two at a time," Nel said. "Johnson must have plotted the entire thing out in his head in advance and then decided what moments to reveal, so that it looks like Harold is improvising the story, but it is not improvised and it's extremely carefully plotted out and very difficult to do."

Regardless, he hopes the movie will make audiences have a better appreciation of the deep simplicity of the genre.

Children's literature, too, is art, and not by accident, Nel said.

"Anyone who has spent any serious time with children's books, whether it's as a reader or as a writer, I think they start to understand that a lot of thought goes into something that is apparently quite simple -- like a boy drawing his world with a crayon.”