There’s a new heart risk calculator coming, and K-State physiologists validated it

Wednesday, Nov. 27, 2024

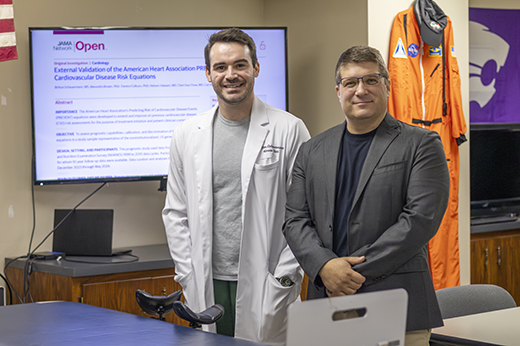

Britton Scheuermann, left, doctoral candidate in Carl Ade's Clinical Integrated Physiology Lab, was lead author on a paper validating the American Heart Association’s new PREVENT equations to calculate patients’ cardiovascular disease risk. | Download this photo.

Britton Scheuermann, left, doctoral candidate in Carl Ade's Clinical Integrated Physiology Lab, was lead author on a paper validating the American Heart Association’s new PREVENT equations to calculate patients’ cardiovascular disease risk. | Download this photo.

MANHATTAN — Cardiovascular disease has long been the leading cause of death around the world, but a new set of predictive scores — validated by physiologists in Kansas State University's College of Human Health and Sciences — will equip doctors and patients with the knowledge they need to make early interventions.

Britton Scheuermann, doctoral candidate, Perrysburg, Ohio, in kinesiology associate professor Carl Ade's Clinical Integrated Physiology Laboratory, was lead author on a paper in JAMA Network Open validating the American Heart Association's new PREVENT equations to calculate patients' cardiovascular disease risk.

The new equations, an update to the heart association's previous models, provide patients 30 years and older and their medical providers with more precise scores that use patient factors like age, cholesterol levels, blood pressure and other metrics to calculate their 10- and 20-year risks of total cardiovascular disease, such as heart attack, stroke and heart failure.

"Our research was to look at these equations and see if they really did accurately predict the occurrence of cardiovascular disease risk, based on actual instances in a database that we used of nearly 200 million participants," Scheuermann said. "In this case, we found these equations do a great job of identifying people at high risk versus low risk, as well as also getting roughly correct estimations of the timeline and occurrences of cardiovascular disease events in different risk categories."

According to Scheurmann, rather than a specific prediction for a specific individual, the scores provided by the PREVENT equations are more like odds of developing or experiencing cardiovascular disease.

"If you have a 10% risk over the next 10 years, that means that 10 out of 100 people who have the same or similar factors as you do will experience a cardiovascular disease event like a heart attack, stroke or heart failure," Scheuermann said.

The scores are further categorized as low risk, or less than 5% likelihood of developing cardiovascular disease in 10 years; borderline risk for 5-7.4%, intermediate for 7.5-19.9% and high risk for more than 20%.

Ade, corresponding author on the paper and Scheuermann's research mentor, said the study does the important work of providing secondary, independent validation of the scores, increasing medical providers' confidence in using them in their patient care as the American Heart Association more broadly rolls out the scores.

"The real challenge for anyone in health care is trying to look in the crystal ball and figure out who is actually at risk for cardiovascular disease," Ade said. "Over the next year or two, with the help of our paper and maybe even others, the hope is that we can show the PREVENT scores are even better, and I think you'll see a trend of practitioners integrating that PREVENT score into electronic health records and daily practice."

Scheuerman's research was carried out in partnership with K-State's Johnson Cancer Research Center, Stormont Vail Health and the University of Kansas Medical Center.